Egg shells are 94% calcite, which amounts to 2.7 g of calcium for a 60 g egg. The calcium mainly comes from the carbonate added to their feed in various forms: powder, granule, animal meal, sea shells, etc. Calcium can also be taken from the medullary bone, an important internal source but one which can quickly be exhausted if calcium is not provided in feed.

The quality of the shell is therefore determined by the quantity of calcium ingested by the animal, but only in part. An amount of coarse carbonate (2-5 mm) is required in order to supplement the intake of carbonate powder (<0.2 mm) and thus allow a

continuous supply of calcium throughout the night.

Despite good management in terms of the quantity ingested and the ratio of coarse/powdered carbonate, in some cases there are concerns about fragile shells which can occur in older hens, but why is this?

This is due to a criterium which is too often overlooked, the solubility of the coarse carbonate! When buying carbonate, you are buying a proportion of calcium and a granule size. It is easy to control in the laboratory and inexpensive. But who asks about the solubility of the carbonate? This solubility can vary

enormously between two quarries. It depends on the chemical composition and structure, which are not strictly identical.

How can we analyse it? The principle is simple, the calcium granules are dissolved in the gizzard of the animal in order to pass into the intestine in the form of a liquid solution during the night. Therefore, we need to create an artificial gizzard = ToC: 41°C, pH: 2 (using hydrochloric acid), with gentle agitation.

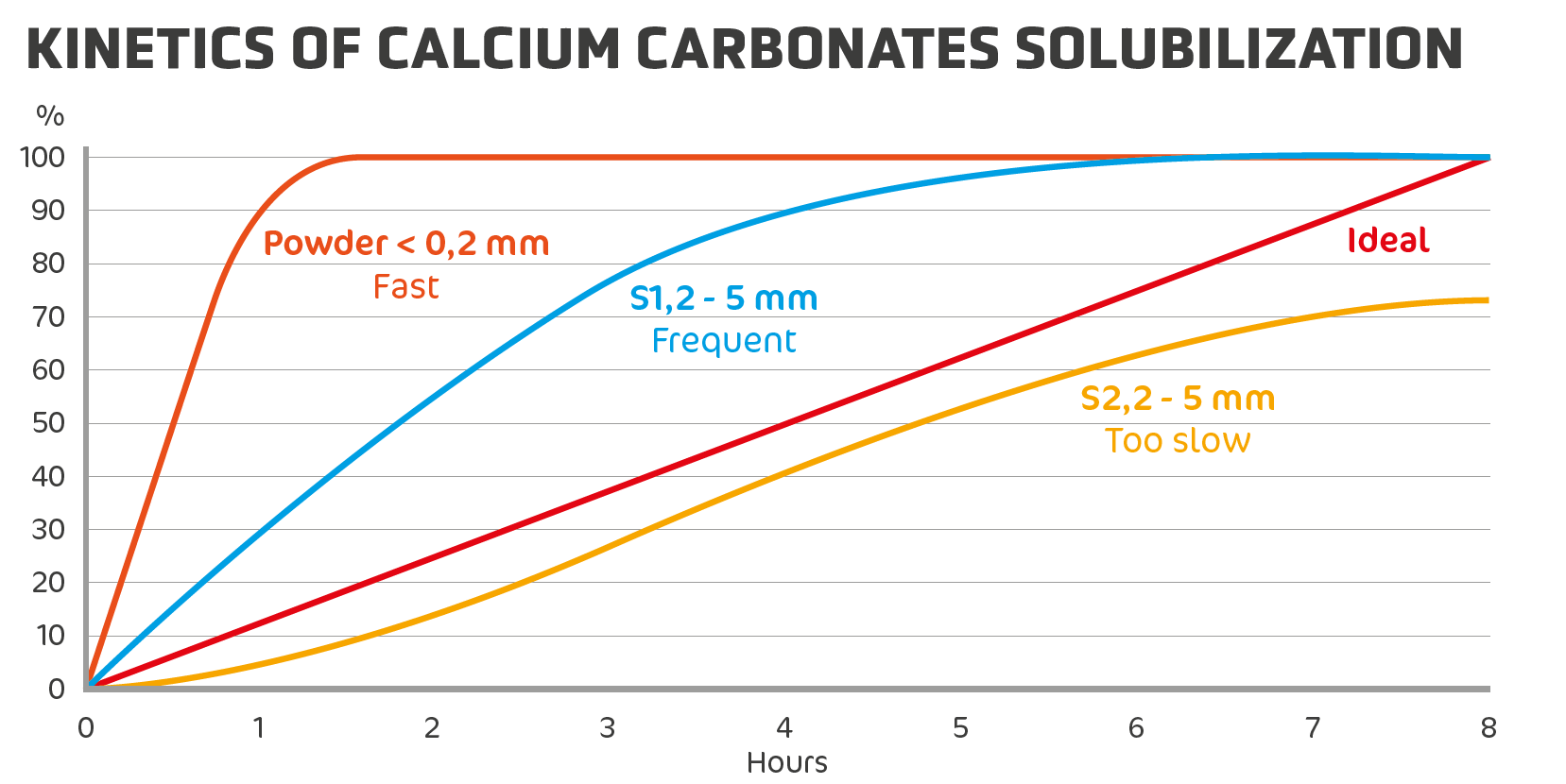

Then, at each set time interval (30 mins, 1 hour, 2 hours, etc.), all we have to do is weigh the undissolved calcium granules (or analyzed the Ca in the water) to obtain the solubilisation kinetics. Solubility can never be determined from a single analysis, it is kinetic!

Once the kinetic solubility is established then, and only then, should you adjust: either the proportion of calcium, the powder/granule ratio, the size of the granules, or how it is managed to optimise the quality of the shells.

Let’s take S1 as an example: a situation that is too often encountered, for 3 hours towards the end of the night, the hens only have their medullary bone to finish making a good-quality shell, all the calcium is already dissolved (the gizzard is empty). Therefore, it is necessary to: either increase the size of the calcium granules to delay solubilisation, or add midnight lighting (local regulations permitting). The aim is to provide the chicken with enough calcium during the nocturnal period (usually 8 hours) to ensure it can preserve the calcium reserves in its bones as long as possible.

Without measuring solubility, you are working blind! It makes it possible to optimally adjust calcium intake in order to optimise shell quality and the state of the batch until the hens become spent fowl.